Chartres Cathedral

| This history is divided into four parts: |

Chronology of Chartres Cathedral |

|

ANNOUNCEMENT

I will be in Chartres July 20-24 to support Robert Ferré's Labyrinth Pilgrimage.

I will be speaking on the cathedral's history, on the symbolism of the Labyrinth and on how the master masons 'saw' their work - with a tour of the upper parts of the cathedral.

If you are interested contact Robert's Labyrinth site.

|

| |

The Master Masons |

|

| |

The Nine Masters |

|

| |

Unity and the Use of Geometry |

|

| |

|

|

CHRONOLOGY OF CHARTRES CATHEDRAL

There have been at least five cathedrals on this site, each replacing an earlier smaller building that had been destroyed by war or fire. It was called the 'Church of Saint Mary' in the eighth century, and in 876 Charlemagne's grandson, Charles the Bald, gifted the Virgin's great relic, the Sancta Camisia, to the cathedral. It is believed to be the one that Mary wore when she gave birth to Christ.

This veil is now housed in the cathedral treasury. The present dedication to 'Beata Maria Assumpta' probably dates from this gift.

The earlier church had been destroyed by the Danes in 858. There was another fire in 962, and a more devastating conflagration in 1020 after which Bishop Fulbert reconstructed the whole building. Most of the present crypt, which is the largest in France, remains from that period.

Fulbert established Chartres as one of the leading teaching schools in Europe. Great scholars were attracted to the cathedral, including Thierry of Chartres, William of Conches and the Englishman John of Salisbury. These men were at the forefront of the intense intellectual rethinking that we call the twelfth-century renaissance, and that led to the Scholastic philosophy that dominate medieval thinking.

In 1134 another fire damaged the town, and perhaps part of the cathedral. The north tower was started immediately afterwards, and when it reached the third storey, the south tower was begun. The sculpture of the Royal Portal was installed with it, probably just before 1140. It was once thought that this sculpture was intended for another place and moved here, but recent investigation has shown that all three doors and the magnificent figures around them were created for their present situation. The two towers were then completed fairly quickly and, between them on the first level, a chapel constructed to Saint Michael. Traces of the vaults and the shafts which supported them are still visible in the western two bays. The glass in the three lancets over the portals which once illuminated this chapel were installed in about 1150. The south spire is 103 meters high, and was completed before 1155.

Finally, on 10 June 1194 another fire destroyed nearly the whole of Fulbert's cathedral. The choir and nave had to be rebuilt, though the undamaged western towers and the Royal Portal were incorporated into the new works, as well as the old crypt. The present cathedral is only slightly longer than the earlier one.

Construction proceeded quickly, with about 300 men on site at any one time. The south porch with all its sculpture was installed by 1206, and by 1215 the north porch had been completed and the western rose installed. The high vaults were erected in the 1220s, the canons moved into their new stalls in 1221, and the transept roseswere erected over the next two decades.

Each arm of the transept was originally meant to support two towers, two more were to flank the choir, and there was to have been a central lantern over the crossing - nine in all. The latter was eliminated in 1221, and the crossing vaulted over. Work continued in a desultory fashion on the six additional towers for some decades, until it was decided to leave them incomplete, and the incompleted cathedral was dedicated in 1260 by King Louis.

Little has been done to the cathedral since then. In 1323 a new meeting house was constructed at the eastern end of the choir for the Chapter, with the Chapel of Saint Piat above that. This is today the cathedral treasury. Shortly after 1417 a small chapel was placed between the buttresses of the south nave for the Count of Vend6me. At the same time the small organ that had been built in the nave aisle was moved up into the triforium where it still is, though some time in the sixteenth century it was decided replace it with a larger one a raised platform at the western end of the building. To this end some of the interior shafts in the western bay were removed and plans made to rebuild the organ there. It was fortunate that this decision was reversed, for otherwise the wonderful glass in the western lancets would have been lost. Instead the old organ was replaced with the new one we know today.

In 1506 lightning destroyed the north spire, which was rebuilt by Jehan de Beauce. It is 113 meters high. He took seven years to carve the intricate and delicate stonework on this tower, and erect it. Afterwards he continued working on the cathedral, and began the monumental screen around the choir stalls, which was not completed until the beginning of the eighteenth century.

In 1757 the jubé screen between the inner choir and the nave was torn down, and the present stalls built. Some of the magnificent sculpture from this screen was found buried underneath the paving, and removed to the treasury. At the same time some of the stained glass in the choir clerestory was removed and replaced with grisaille, or grey glass, so that the canons could read their missals more easily. Then in 1836 the old lead and timber roof, known as the forest, was burnt out and rebuilt with copper sheeting on cast iron supports - at its time the larges span on the continent.

The cathedral has been fortunate in being spared the damage suffered by so many during the Wars of Religion and the Revolution, though the lead roof was removed to make bullets and the Directorate threatened to dynamite the building as its upkeep, without a roof, had become too onerous.

All the glass was removed just before the Germans invaded France in 1939, and was cleaned after the War and releaded. Since then the fabric has been lovingly tendered and repaired in a most scrupulous fashion to retain its original character and beauty. |

|

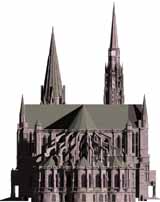

These brilliant images were prepared by

Ruedi Segessemann.

I no longer know how to contact him to thank him for these images, though I did find an out-of-date web page.

Ruedi, are you out there???

Chartres from the east

Chartres from the west, both externally and from inside.

|

|

40% discount for wholesale.

|

|

|

|

$50

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

$25

|

|

|

|

$100

|

|

|

|

two vols. $1,500

|

|

|

|

two vols. $250

Prices in Australian dollars

|

|

|

Chartres south elevation

Chartres north elevation

Chartres apse exploded so you may study the whole complex arrangement from a worm's-eye view. Only the piers have been omitted.

Bird-eye view of Chartres nave from south-west.

|

|

THE MASTER MASONS

Too many of the great cathedrals have been destroyed by fire, desecrated by restorers and bigots, and their glass and sculpture wantonly hacked out. Anger, calamity and stupidity have taken all too great a toll. We are fortunate still to have at Chartres an almost untouched thirteenth?century cathedral, with the most marvellous assembly of images in Europe, a collection of stained glass without equal in the world and, in total, an enduring encyclopaedia of Christian thought.

The cathedral built after the first fire was almost as large as the present building, and at the time the second largest church in Europe, the first being Saint Peter's in Rome. Remnants still embedded in the towers suggest that it was three storeys, with a middle gallery, and that it was almost as high as the rose windows in today's clerestory. An immense building indeed.

During one terrible night in 1194 a disastrous fire raged through the town of Chartres, laying waste most of the houses and shops, and destroying much of its ancient cathedral. As the smoke abated only the western spires remained above the charred and tattered walls. A desolate picture! Surmounting their despair the townsfolk and the clergy decided, in the most positive way, that the fire had been a sign from the Virgin herself, an injunction to rebuild Her House in the most marvellous manner possible.

For this they invited an architect from the region to the north-east of Paris, a talented man who had worked for the Cistercians and the Benedictine monks, as well as at the cathedral of Laon. He seems to have been a seriously philosophic man, skilled as a mason and with a considerable understanding of the Christian theology of his day. We do not know his name, for all the documents have been lost, but we have identified him in sufficient places to gain some idea of his standing and capacities. Lacking a documented name, I called this genius 'Scarlet'.

A dozen years earlier he had begun the apse in the huge Cistercian Abbey of Longpont. This austere order imposed strict limitations on the masons who worked for them; but it seems that Scarlet may have influenced his patrons, for the plan of Longpont was unusual for the 1180s. Instead of the usual flat eastern end, Longpont has an ambulatory with seven chapels not unlike the plan Scarlet prepared for Chartres a little later.

Scarlet did not work long on the Chartres site, for the entire cathedral was constructed by teams of roving contractors who seem to have worked for as long as there was money, and then moved on to other sites. Nine major teams were involved it this great task. Though Scarlet's design influenced every master who followed him, each new master imposed his ideas on the cathedral plan whenever he could, and continued with his predecessor's concepts when he could not.

All this is described in my book, The Master Masons of Chartres. To see a description of the book, or to order it, click here.

In spite of the constant coming and going of these different teams' of men nearly the whole of the cathedral was completed in thirty short years.' building teams were large, perhaps consisting of 300 men, of which 50 would have been skilled masons and the key men in charge of the organization. This number could not have been left idle while the church waited for donations. Once the coffers were empty they would have left the site in a body, and found other employment. When enough money had collected to allow the church to re-engage masons, the last group was probably working at some other site, and a fresh team had to be found. Impermanency was normal, and everyone expected it.

There were also technical considerations, like the slow-setting lime mortar that could force the builders to leave. Even in the Royal works, where there were ample funds, builders were put off while the mortar set in the voussoirs of the arches or vaults. At the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris there may have been as many as five changes to crews for just these technical reasons. Changes in masters were expected by both the owners and the masters themselves. Their methods of design were evolved to cope with this situation, and to ensure that enough unity would be maintained between the working mason and his successor to prevent the design becoming totally chaotic.

This was a time of extraordinary building activity across the limestone region we call the Paris Basin. Over 2,700 churches, chapels and cathedrals were built in this small area during the one century that separated the choir of Saint-Denis from the Sainte-Chapelle. Over 90 percent of all Early Gothic churches are found in the Paris Basin because it was here, and practically nowhere else, that the revolution in architecture was occurring.

A recent analysis of the costs of this ecclesiastic work showed that the quantity of building in the north around Soissons and was greatest in the 1170s and 1180s, while in the Ile-de-France construction peaked around 1220. While the Soissonais was a-bubble with great buildings, churches in the area around Paris were relatively modest. It was in the north-east, therefore, that construction teams were assembled and trained. After 1190, as work declined in the north-east, these skilled men, complete with their followers, travelled great distances looking for work, and Chartres was one of them. And this is why most of the other buildings executed by the contractors who built Chartres are to be found to the north of Paris between Senlis and Reims.

|

THE NINE MASTERS

My research has shown that there were nine groups, or teams of masons, each under the control of one master mason, with their attendant quarriers, apprentices and so on. These teams, which may have numbered as many as three hundred men, seem to have arrived on the site as a group, and left together: the carving styles change at the same time as the architectural details.

The unusual aspect of the medieval building process, which applies to the smallest church as much as to the greatest cathedral, was that these teams seldom stayed on the site for very long. One might work for a few months, the next for a couple of years, in an ever changing sequence that lasted throughout the many decades needed to construct the cathedral.

The first master we have named Scarlet, since we did not know his name; he began work just after the fire in 1194. The second was Bronze and the third Olive, working around 1196. Probably in 1200 Scarlet returned to set out the south porch and the labyrinth. Olive returned some ten years later to redesign the clerestory windows, and the team we call Bronze worked nine times on the site between the fire and the completion of the main vaults.

For over thirty years the masters changed almost every year. The cause was probably money: they did not have the sophisticated funding techniques we possess, but relied on cash, and when there was money the hand work could be pushed on apace - but when there was none the builders ad no choice but to pack up and find work elsewhere. And this they did.

Olive, for example, worked mainly along the Marne river, and at Rheims and Soissons, and on only three occasions moved out of this region to work at Chartres. Most of the work by the Bronze team is to be found in the hill district between the Aisne and Laon, though his characteristic style is to be found as far away as Mantes-la-Jolie, as well as at Chartres.

It is by their style that we recognize them. This most exciting aspect of this research is identifying the hitherto anonymous architects of the Middle Ages by what we might call the thumb-print of each person. Every master had a unique approach to his profession, with his own way of creating the profiles and of arranging them into elements like windows and doors. Though there were changes with the passing years, each master's personal style tended to remain distinctly his during his lifetime.

There are still many gaps in our knowledge, but it is becoming increasingly clear that the extraordinary architectural inventions manifested during the century around 1200 stemmed from the creative endeavours of a few dozen men who travelled across great distances with their workmen. They gained an intimate understanding of their fellows by constantly being asked to continue with buildings which had been reared by others, yet every one of them maintained a strong, often idiosyncratic, manner of working that identifies him as clearly as the lines on our hands will identify us.

|

|

More by Ruedi.

Chartres from north-west

Chartres from south-east

|

Typical nave bay.

Labyrinth in the nave

south porch disected.

south porch from the front

|

|

UNITY AND THE USE OF GEOMETRY

Yet, in spite of the way they worked, and the coming and going of the masters, there is an overall sense of oneness about Chartres. It seems, to our eyes, a unified work in spite of the discrepancies. The reason for this lies in their design methods.

The design of the elements, like the piers and windows, were all determined from the first parts laid out. The width of the window openings, which also determined the width of the column of light that floods into each bay of the aisles, was made the same as the thickness of the piers. It was as if the master measured the overall pier size, and used that to fix the glass width. The result was quite extraordinary: the solids which support the vaults alternate with the luminous openings, forming a contrapuntal harmony down the length of the nave. Mass and void have been placed in a sublime artistic balance. The thickness of the pier from which the width of the windows was determined was itself evolved from the dimensions of the bay and span, so that the distances between the axes both down the aisle and across the space of the nave were used, albeit in a somewhat complex way, to create the pier placed on the intersection of these axes.

In a similar way every element in the elevation was derived, or 'extracted' in medieval parlance, from the plan. The width of the windows was one felicitous example of this. Another is the spaces in the aisle, where the voids, measured between the piers, and between pier and wall shafts, form a relationship of the Golden Mean, that ancient ratio which underlies the proportions of most growing things

How this worked in practice is that when the work had progressed to the height of the capitals, the master took a rod of wood and cut it so that it exactly fitted between the piers. It therefore represented the Golden Mean ratio itself. He then used two of these rods, placed end on end, to locate the tops of the capitals. Thus, automatically the Golden Mean proportion used in the plan came to be repeated in the elevation.

Chartres is recognized as a beautiful building not only because this proportion occurs in the public spaces, but also because later masters continued to use dimensions found in the aisles at all levels of the building, including the overall height of the main vaults.

So today, when we walk down the aisles of the nave, we experience these perfect proportions. It may be bizarre, but the master who located the capitals need not have known that he was thereby producing this classic proportion. It is the beautiful consequence of this method that, by determining the parts of the elevation from lengths derived from elements in the plan, the proportions used in the plan will automatically occur in the façade. No further calculation would be necessary, and though the masters did continue to calculate proportions for the vertical dimensions, there was no need for them to do so as long as they followed the method.

In nearly all these churches we need to use our imagination if we are to have much feeling for what they were like a thousand year ago. We see then bare, the plain stone walls and piers occasionally retaining a scrap of paintwork. In the north side of the choir at Chartres the altar of the Virgin may give some idea of what they were like. It is surrounded by candles, often hundreds of them, as every chapel and every altar would have been in the Middle Ages. The gold on the altars and precious stones mounted on the reliquaries shone with an eerie iridescence, the copper and bronze of the giant candelabras reflected the candles, and over all hung the lazy plumes of incense.

The interiors were like jewels themselves, reflecting the words of Saint John that the Heavenly Jerusalem 'was of jasper: and the City was of pure gold, like unto clear glass. And the foundations were garnished with all manner of precious stones.

The effect is peaceful and nurturing. We are at rest, without being immobilised or being over-stimulated. We are left to wander or to meditate in tranquillity. These immense structures exemplify the very essence of the period: mystic and immanental, secure in the knowledge that God is very near. The buildings seem to levitate just a little so that for one short magical moment the tabernacle seems to occupy the entire material edifice. It is like a temple hanging within the walls of a fortress.

The walls were hung with tapestries, carpets and ruches covered the paving, and of course the disarming glow of stained glass suffused everything. There was always music. Large choirs and many musicians were always employed, not only for the masses themselves, but for the processions of relics. Important visitors would be heralded by fanfares and songs of welcome. The church was alive and the focus of all activity in the area.

One feels so secure at Chartres that the verticality combines with the sense that this is Paradise itself to suggest that the barrier between us and it, between the human and the celestial, has disappeared. The impact of Chartres on people at that time was enormous. More than any other building, it represented an ideal. It rose to the status of an icon, simultaneously divine and material.

|

|